by Joe Russo

December 7, 2015

From Barbarossa to the Kingdom of Sicily

(Lipari 1544 – 1610)

A couple of generations after Barbarossa sacked Lipari in 1544, the first comprehensive census was taken. The year was 1610. Lipari had recently become part of the Kingdom of Sicily after being part of the Kingdom of Naples since 1458.[1] By this time, the generation that had witnessed the devastating events of 66 years earlier – the few that survived or managed to return – had virtually all passed from the scene as was the generation that arrived immediately afterwards.[2] What we will look at in this article is the period between these two dates and what the census reveals about the population in 1610.

The changing nature of Lipari’s population

Before we get to 1610, let’s get an overview of what  was happening during the intervening 66 years since Barbarossa. The Spanish came, set up a garrison=presidio and reinforced the city’s fortifications. While they provided protection, immigrants were incentivised to settle on Lipari while others returned, arrived due to trade or their skills were required in the rebuilding of Lipari. New surnames were introduced.

was happening during the intervening 66 years since Barbarossa. The Spanish came, set up a garrison=presidio and reinforced the city’s fortifications. While they provided protection, immigrants were incentivised to settle on Lipari while others returned, arrived due to trade or their skills were required in the rebuilding of Lipari. New surnames were introduced.

We are told that those who evaded capture or returned were few in number.

Invero, proprio nel 1544, pochi furono i Liparoti che sfuggirono ai pirati e pochi furono quelli che sottrassero alla schiavitù e tornarono in “patria”; parecchie, invece, furono le persone provenienti dalla Calabria, dalla Campania e soprattutto dalla Sicilia che si stabilirono a Lipari tra il 1544 e il 1550 e negli anni successivi.[3]

Indeed, precisely in 1544, few were the Liparoti who evaded the pirates and not many those who escaped from slavery and returned to their homeland; many, instead, were those who came from Calabria, Campania and above all Sicily who settled on Lipari between 1544 and 1550 and the following years.”

Actually, we do not really know the origin of those who arrived on Lipari during the first decade after Barbarossa. It’s not until later that church records start consistently documenting the origin of the people who were not native born. This is when we learn Calabria and Sicily as the homeland for the majority of Isole Eolie’s new residents. However, it is not inconsistent that the earlier migrants should also be from here.

Angelo Raffa reaches the same conclusion:

Dei genitori di costoro (cioè dei primi immigrati, nel periodo dei primi decenni dopo il 1544) non conosciamo, naturalmente, la provenienza.[4]

Of their parents (that is of the earliest immigrants, from the first decade after 1544) we do not know, of course, where they came from.

Beyond the city of Lipari

As the population grew, the people started moving to the towns further away from the city, and, as a consequence, churches, chapels or oratories were built in those locations. Churches get built where there are people for the church to service. If there are no people living there, then there is no need to build a church or a chapel. By looking at when these churches were built, we can assume there must have been a small community living in those towns at that time. In 1545 three churches rose up and in the space of 27 years (1569-1596) 18 more churches/chapels were built throughout Lipari.[5]

and, as a consequence, churches, chapels or oratories were built in those locations. Churches get built where there are people for the church to service. If there are no people living there, then there is no need to build a church or a chapel. By looking at when these churches were built, we can assume there must have been a small community living in those towns at that time. In 1545 three churches rose up and in the space of 27 years (1569-1596) 18 more churches/chapels were built throughout Lipari.[5]

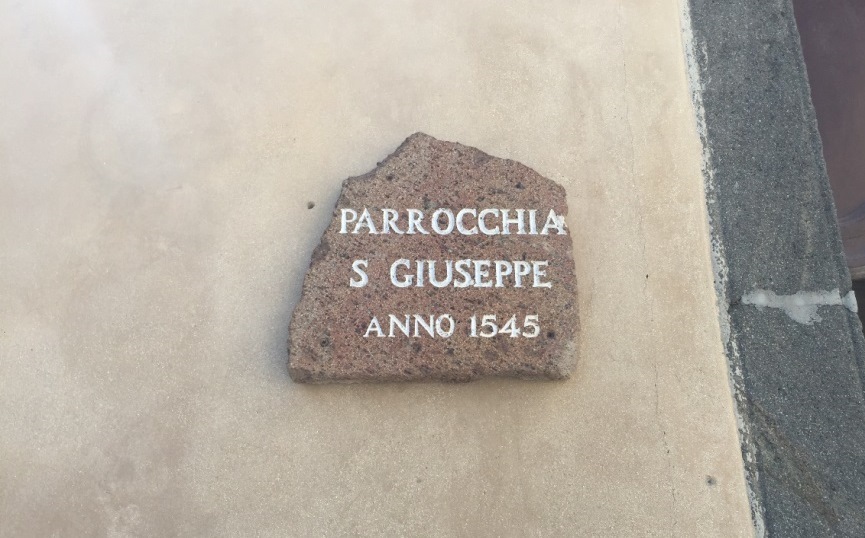

Some churches on Lipari and when they were founded:

- Lipari

- San Giuseppe 1545

- San Pietro 1545

- Sant’Anna 1569

- Santa Caterina 1579

- San Francesco(Sant’Antonio) 1585

- Serra 1579

- Pirrera 1588

- Quattropani 1588

- Pianoconte 1593

- Canneto 1594

The entire island of Lipari had been repopulated to some degree by the turn of the century.

On Salina, there wasn’t much of a presence before the turn of the century.

- Rinella 1602

- Capo 1606

- Lingua 1612

- Valdichiesa 1622

- Santa Marina 1622

- Malfa 1632

At the time of Barbarossa, Jérome Maurand tells us Salina was well cultivated with vineyards and their produce was sold as far away as Constantinople.

. . . Saline, dove sono belissime vigne, non de uve per far vino, ma sollo da far zebibi; dove se ne fa en grandissima quantità, de li quali li mercanti ne portano fino in Constantinopoli. [6]

. . . Salina, where there are beautiful vineyards, not grapes to make [any] wine, but only to make zebibbo; where they make a great quantity, which the merchants export even to Constantinople.

In 1573 the Bishop of Lipari, D. Pietro Cavaliero, issued an order that no one was to go to any of the other islands without written permission from him with the penalty being excommunication. The edicts were continued by other bishops in 1581 until 1622.[7] The church needed to monitor what was grown and caught on the islands and receive its decima=a tenth of the revenue.

Di più, nel medisimo anno 1573, Monsignore D. Pietro Cavaliero Vescovo di Lipari fece ordine fulminatamente che nessuna persona avesse ardire di andare a nessuna Isola – come Salina, Vulcano, Alicudi, Filicudi, Strongoli, Panarea – senza licenza in scriptis di esso monsignore . . . .[8]

Moreover, in the same year 1573, Monsignor Don Pietro Cavaliero Bishop of Lipari enacted an order that nobody should dare go to any island – like Salina, Vulcano, Alicudi, Filicudi, Stromboli, Panarea – without a written permit from him. . . .

and (1581)

So che Don Pietro Cavaliero Piscopo di questa Città fece bandire nella ecclesia una scomunica che nessuna persona andasse all’isola della Salina senza una expressa licenza scritta e poi la fece attaccare alla porta della madre Chiesa . . . .[9]

I know that Don Pietro Cavaliero Piscopo of this city proclaimed in church an excommunication that no one should go to the island of Salina without a written permit and then had it attached to the door of the mother church. . . .

By 1595, during Bishop Giovanni Gonzales de Mendoza’s tenure (1593-1598), Salina was being cultivated for the church (‘ora comincia ad essere coltivata=now it begins to be cultivated’).[10] The census in 1610 only mentions a few people and the church as owning land on Salina.

Dai riveli infatti risulta che la Chiesa liparitana possedeva vari fabbricati (chiese, palazzo vescovile e qualche casetta) dentro la città di Lipari e che aveva la piena proprietà o era proprietaria direttaria di fondi siti a Salina e in varie località dell’isola di Lipari . . . . [11]

From the census we learn that the Church in Lipari owned various buildings (churches, bishop’s residence and several small houses) within the city of Lipari and it had the full ownership or was the lessor of land on Salina and in various locations on the island of Lipari.

Whatever presence there was on Salina was therefore few in number and/or seasonal in nature with the inhabitants returning to Lipari.[12]

The other islands were uninhabited, or at least there weren’t any settled communities during the second half of the 1500s, with no one owning cultivable land.

Nulla dicono i riveli circa le altre isole dell’arcipelago, però, per l’esattezza, anche queste vanno incluse tra i beni immobili di cui la Chiesa di Lipari vantava la proprietà sulla base delle concessioni normanne del 1088 e del 1134 e della bolla di Urbano II del 1091. . . Nulla risulta dai riveli circa la distribuzione della terra coltivabile a Vulcano, Stromboli, Panarea, Alicudi e Filicudi. [13]

The census says nothing about the other islands of the archipelago, but, to be exact, even these are included with the property owned by the Church of Lipari according to the Norman concessions of 1088 and 1134 and the papal bull of Urban II of 1091. . . There is nothing in the census about the distribution of cultivable land on Vulcano, Stromboli, Panarea, Alicudi and Filicudi.

The church records

The Council of Trent (1545-63) established every parish priest was to maintain written records of baptisms, marriages and deaths of all parishioners. [14] So for Lipari, we have baptisms beginning in December 1559, marriages from 1594 and burials from 1651. Although some years don’t have a complete set of records, we can still draw some reasonable conclusions.

Chart 1: Total Lipari Births 1560-1610 (*adjusted for incomplete years 1586, 88-93, 1599-1601).[15]

From this chart of births, where I have made some adjustments when the records don’t cover the full year, we see during the 1560s it averaged around the 40-50 births/year but a couple of generations later into 1610 there were over 140 births/year – three times that of the earlier period of the 1560s. Now, we don’t know how many births there were prior to 1560 because no records exist. Nor do we know how many died during this period nor how many people migrated and settled on Lipari. So any calculation back to 1544 is at best an estimate.

The Census

The census covers a lot of aspects that we will not cover in this article. We are not going to be concerned so much with the resident’s possessions, the distribution of their wealth, or how many animals they owned. We are interested in the statistical make-up of the population. Giuseppe Arena analysed the 1610 census that is kept at the Palermo Archives and documented it in his book Popolazione e distribuzione della ricchezza a Lipari nel 1610. The following figures are from his book. [16]

The author differentiates between residents and those present on Lipari at the time: [17]

1) The population present during the census was 2647 [18] and included.

- Those of native origin.

- Those who arrived from elsewhere but had attained Liparoti citizenship and were present on the island.

- Foreigners who were present during the census (but were not citizens).

2) The resident population during the census was 2384 and, compared to the present population, excluded.

- Spanish soldiers (including their families and servants).

- A few others who happened to be there primarily on business.

- But includes residents who are noted as absent during the census (mariners, on business, and ‘i sequestrati’ (taken captive by pirates).

We shall alternate between the present and resident population depending upon which facts and figures are better supplied to us. For example, there is a better analysis of the resident population than there is of the population present. Some figures refer only to the male population because quite often a woman’s age is not given; neither is it for the clergy.

Here are some figures.

- Present population 2647 of which 1402 male and 1245 female.

- Resident population 2384 of which 1281 male and 1103 female.

Charts 2a/b: Lipari’s Population in 1610 (percentage of males and females)

- 2 medical doctors (Giovanni Russo and Jacovo Canali).

- 4 doctors of law and 4 notaries. In other words, 8 qualified in law and only 2 in medicine for the entire population.

- 9 people who did not own anything. There are also quite a few people listed as servants, apprentices, or living with other family members. These people probably didn’t own any taxable possessions or land of their own as they lived with someone else.

- 11 orphans.

- 22 average age of resident non-cleric males with only 15% of the male population over 40. Although we can’t calculate it, the female population probably had a similar demographic distribution.

Chart 3: Total number of non-cleric resident males per age group.

Chart 4: Total number of non-cleric resident males per age group.

- 38 Slaves.

- 45 priests, 8 Frati Minori Osservanti (Franciscan Order) and 18 nuns (71 clergy, 92 including their families and servants living with them).

- 57 soldiers (256 including their families and servants).

Chart 5: Population present during the 1610 census.

- 88 servants (excluding slaves and clerics at the service of higher clergy); 75 males and 13 females.

- 91 inhabitants/km2 (density of Lipari).

- 391 married couples for the resident population (of which four husbands were absent during the census) and excludes non-resident married soldiers (total of 47, three of whom were married to residents of Lipari).

- 822 single males and 550 single females (excludes priests and nuns).

Charts 6a/b: Lipari’s resident population by marital status.

Conclusion

In 1544 few people were left after Barbarossa sacked Lipari – perhaps a few hundred at most – to repopulate the island. By the beginning of the 1600s the entire island of Lipari had been repopulated to some degree with churches appearing throughout the island. The population expanded such that in 1610 there were 2384 residents and 2647 present during the census of that year. This is not a lot of people – little more than the population of Salina today. Not many people owned or worked the land outside Lipari. Salina was primarily cultivated for the church and the smaller islands were uninhabited and uncultivated. The population was young, a large proportion of them unmarried, and few soldiers (excluding their families) were present. The figures provide a good analysis of how far Lipari had come in a couple of generations and with a high growth rate gave it a solid foundation for future growth in the years ahead.

Endnotes

[1] Giuseppe A.M. Arena, Popolazione e distribuzione della ricchezza a Lipari nel 1610, (Società Messinese di storia patria, 1992), p.7; Leopoldo Zagami, Le isole Eolie tra leggenda e storia, (Pungitopo, 2006), pp.234, 267; Pietro Campis, Disegno historico o siano l’abbozzate historie della nobile e fidelissima città di Lipari, ms. del 1694, published with notes by Giuseppe Iacolino (Bartolino Famularo, 1980), p.276. Lipari became part of the Kingdom of Sicily on May 30, 1610.

[2] Arena, op. cit. There were only 15 people 66 years or older of which two were over 80 of 2647 in total present during the census. Those who arrived during the first decade as adults (minimum in their 20s) would have been at least mid-70s and older. In other words, there were only a few who could remember the events of 1544.

[3] Ibid., pp.23-24. Arena draws on Campis’ reference that after Don Pietro di Toledo, Viceroy of Naples, restored the ancient privileges to Lipari and “…perlochè dalla Sicilia, dalla Calabria e da molte Città dell’Italia vennero buone famiglie ad habitarvi” (…for that reason from Sicily, Calabria and from many Italian cities came good families to live here.) (Campis, op. cit., 164v, p.307).

[4] Angelo Raffa, “La fine della Lipari medioevale”, in Dal “constitutum” alle “controversie liparitane”, Quaderno del museo archeologico regionale eoliano, 2, 1998, p.103, col.1.

[5] Giuseppe Iacolino, Raccontare Salina, Vol.II, (Mario Grispo Editore, 2010), pp.154-155. Some dates vary depending on the source. For example, the façade of the church in Canneto (San Cristoforo) shows the founding date as 1594 whereas Iacolino has 1596.

[6] Jérome Maurand, La Flotta di Barbarossa a Vulcano e Lipari nel 1544, (P. Orsi edizione, 1995), Cap. XI, [p.2].

[7] Iacolino, op. cit., pp.159-162.

[8] L. Genuardi e L. Siciliano, Il domino del vescovo terreni pomiciferi dell’isola di Lipari, (Arcireale, 1912), p.82, no8., quoted in Iacolino, ibid., p.159.

[9] AVL, Libro dei testimoni (1581-1606), manuscript, f.22 v., quoted in Iacolino, op.cit., p. 160.

[10] Iacolino, op. cit., p.173.

[11] Arena, op. cit., p.41. proprietaria direttaria = chi è proprietario di un fondo dato in enfiteusi (where the lessee was required to improve the land and pay an annual fee in either money or agricultural produce).

[12] Baptisms and marriages are recorded in Lipari during this period.

[13] Arena, op. cit., pp.160, 42. Even Ustica wasn’t colonised until the 1760s due to the fear of piracy – the initial settlement in 1761-2 was raided by pirates and most were either killed or enslaved before the island was refortified by soldiers from Palermo followed by a second settlement in 1763.

[14] Trafford R. Cole, Italian Genealogical Records, (Ancestry Incorporated, 1995), p.100; “Italy Church Records” on FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Italy_Church_Records, viewed October 2015.

[15] Chart prepared by Joe Russo. Data derived from LDS Microfilm 1338513, Lipari Baptisms 1559-1696, adjusted for incomplete years 1586, 88-93, 1599-1601 to better reflect births for the full year. This is not a net total and therefore excludes deaths during the same years.

[16] Arena, op. cit., pp.24-28, 59, 81-93. Pie charts for the 1610 census prepared by Joe Russo from data derived from Arena.

[17] Ibid., pp.16-18.

[18] Raffa says there were 2659 inhabitants: “…dai riveli del 1610 risulta che gli abitanti di Lipari erano 2.659.” (…from the census of 1610 the inhabitants of Lipari were 2,659), Raffa, op. cit., pp.102-103.

Joe, You are doing a fantastic job.

Congratulations Joe, brilliant and informative article.

Joe – Exceptional! Maria

PS where can one access the census – would love to be able to do so mcs

Wherever you can find a copy of the book noted above (now out of print) otherwise at the Palermo State Archives.

Hi Joe,

A great piece of work! Congratulations! Easy to read, easy to follow …..

I can see that you’ve spent hours and hours researching this topic! Thank you for sharing with us. Ginette

Hi Joe, a great piece of research and reporting. A fantastic read.

Have you come across a list of families that left Lipari to repopulate Ustica in 1763? It’s a point of interest for me.

Regards

Steve

Thanks Steve. The book L’isola di Ustica by Giuseppe Tranchina covers the topic on Ustica’s earliest inhabitants. However, given the nature of his list, you’ll need to complement it with other sources such as church and civil records to determine exactly who they were so you can then trace them back to Lipari.

Nice to meet you Joe and thanks so much for sharing the resaults of such interesting research. Just like Steve I am after a list of the first families that left Lipari, but this time to Stromboli. As per oral tradition my father, who studed the genalogy of many Strombolian families amongst his own, believed that the Moleta family left Lipari towards Stromboli sometimes after de 1700’s although they might have been originally from Spain. Is there any way to find out where all this families came from ? Unfortunatelly I can not find the book by Giuseppe A.M. Arena, “Popolazione e distribuzione della ricchezza a Lipari nel 1610”. I would be an interesting read for us desendants of the old Aeolian Islands families. All the best, Cristina

Very interesting stuff! I look forward to learning more! Thanks Joe!

Excellent. Some of this most interesting material should be posted in the Filicudari group especially the happening of 1544.

Keep up the good work.

As a descendant of Lipari-to Ustica-to New Orleans families, a hearty thank you for your research and the resources you provide on this site.